The China macroeconomic wrap-up for Q3 2024: Bad, but better than expected

Executive summary

- Real GDP grew by 4.6% y/y in Q3, down slightly from the 4.7% expansion in Q2.

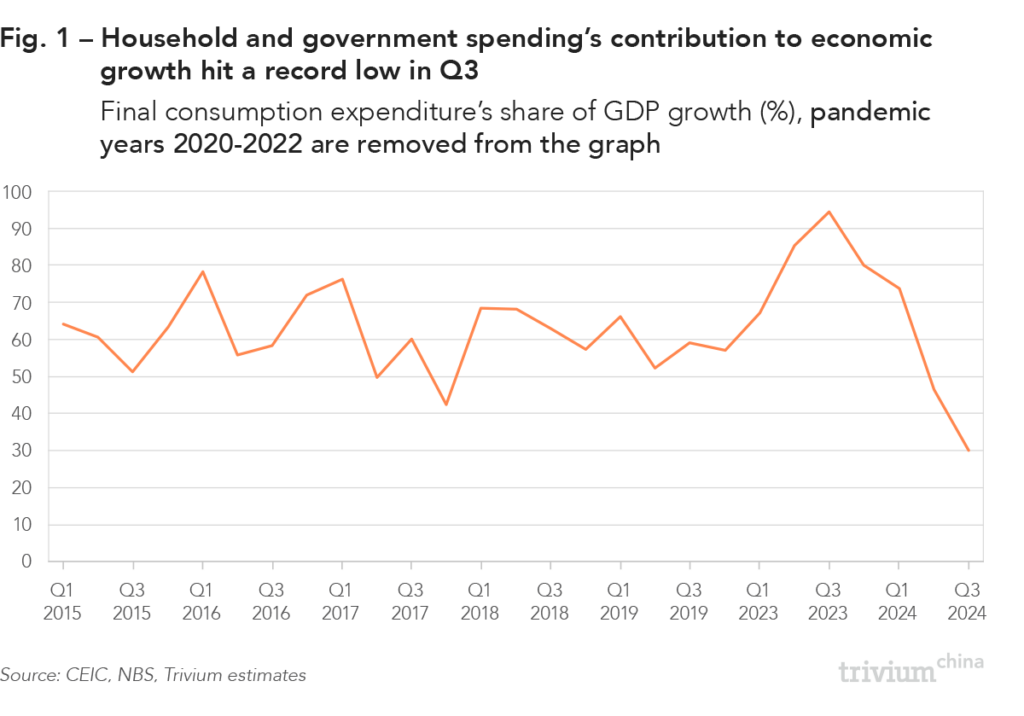

- More concerning, however, is the sharp decline in the quality of growth: Final consumption – which includes household and government spending – contributed just one-third of GDP growth, marking the lowest share on record, outside of zero-COVID.

- Nominal GDP – which includes price effects – grew by 4.0% y/y. That marks the sixth consecutive quarter where nominal growth has lagged real growth, a symptom of deeply embedded deflationary pressures.

- Despite this, business activity – both industrial output and business investment – performed well, particularly in the private sector.

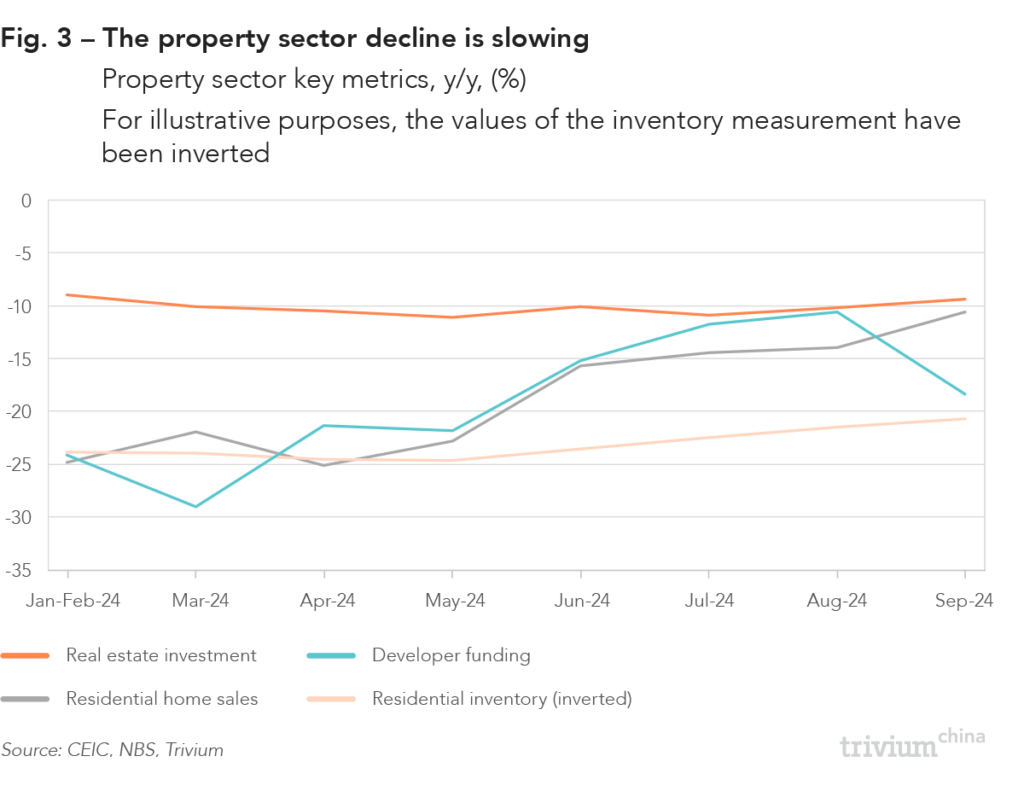

- The property decline – although remaining the biggest drag on growth – is slowing. Key real estate metrics showed a more modest decline in September than in August.

- Investors and businesses are waiting for Beijing to roll out an aggressive fiscal stimulus to boost economic growth and buoy confidence. So far, however, the government has failed to communicate whether there will be such a stimulus, when it will arrive, and how big it will be.

- If the government’s support disappoints – as it so often has this year – China’s economy will continue to underperform, and equity markets will quickly drop.

China’s economic growth slowed a notch in Q3, weighed down by weak consumer spending and the decline of the property sector. Despite this, business activity – both industrial output and business investment – performed well, particularly in the private sector. Economic momentum saw a modest uptick in September, positioning policymakers to consolidate these gains through aggressive fiscal stimulus. Yet nothing of substance has materialized – leaving all eyes on Beijing.

Real growth outpaces nominal growth – again

Real GDP grew by 4.6% y/y in Q3, down slightly from the 4.7% expansion in Q2. More concerning, however, is the sharp decline in the quality of growth: Final consumption – which includes household and government spending – contributed just one-third of GDP growth, marking the lowest share on record, outside of zero-COVID. This is a shocking statistic, considering that before the pandemic, final consumption accounted for about two-thirds of economic growth [Fig 1].

Trade was the biggest growth driver in Q3, accounting for 42% of economic expansion. However, with trade tensions growing, relying on exports to juice the economy is an unsustainable strategy.

On a quarter-on-quarter basis, Q3 GDP grew 0.9%, up from 0.5% growth in Q2. The sequential uptick in growth momentum is a welcome development, but q/q growth remains well below trend levels.

Nominal GDP – which includes price effects – grew by 4.0% y/y.

- That marks the sixth consecutive quarter where nominal growth has lagged real growth, a symptom of deeply embedded deflationary pressures.

Year-to-date, average consumer prices have risen 0.3% y/y, while the price of goods has declined 0.1%. Deflation is even more prominent on the producer side, where factory prices have fallen for 24 consecutive months.

Private sector activity picks up pace

Despite these price pressures, China’s industrial juggernaut continues to churn out goods.

- Industrial value-added (IVA) grew 5.4% y/y in September, up from 4.5% the previous month.

- Month-on-month, IVA expanded 0.59%, marking the fastest m/m growth since April.

Traditional areas of industry – dominated by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and heavily dependent on the property market – are plummeting:

- Production of cement in September dropped by 10.3% y/y.

- Manufacturing of crude steel and steel products fell 6.1% and 2.4%, respectively.

Meanwhile, high-tech manufacturing and auto production were both up from August, expanding by 10.1% and 4.6% y/y, respectively. Importantly, these industries are dominated by innovative private sector firms.

The headline IVA figures highlight the divergence in performance between SOEs and their private sector counterparts: IVA from SOEs grew just 3.9% y/y, while private IVA increased a punchy 5.6%.

Private enterprises are also ramping up investment, with their non-property-related fixed asset investment growing 7.1% y/y in September, the fastest rate since March.

Consumers aren’t consuming

Retail sales grew 3.2% y/y in September. While this is a bad print, it is better than expected, and an improvement on August’s 2.1% growth.

- Month-on-month, retail sales increased 0.39%, which is also up from August.

- On an annualized basis, that equates to 4.8% growth – again, bad, but better than expected.

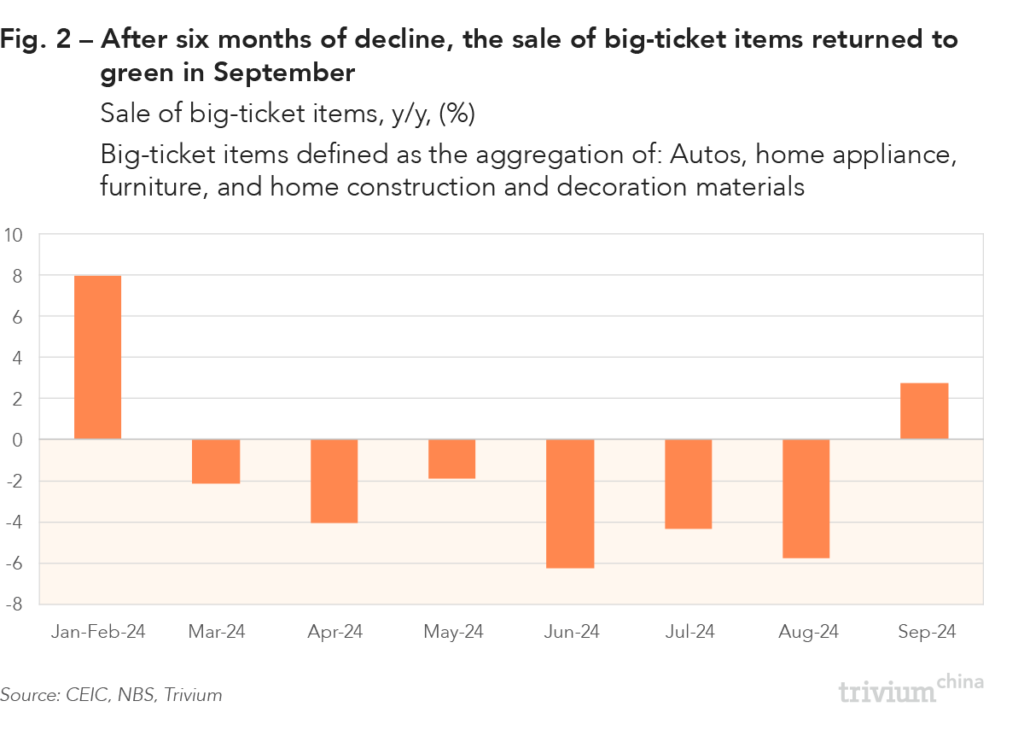

While retail sales were sluggish, sales of big-ticket items finally returned to green [Fig 2].

- Household appliances grew an astonishing 20.5% y/y, after Beijing ramped up its consumer trade-in initiative.

- Furniture sales grew 0.4%, reversing two months of decline.

- Promisingly, autos sales grew 0.4% y/y, halting a six-month decline.

The fact that a 0.4% increase in auto sales is considered a positive development highlights just how weak the economy is. Consumer confidence remains near record lows, driven by the declining property sector and slowing income growth.

- In Q3, real disposable incomes grew 4.1% y/y, the slowest rate since Q1 2023.

- Consumption expenditure grew by 2.7% y/y, the slowest rate since Q4 2022, when the economy was still under zero-COVID controls.

The property sector decline is slowing – slowly

In last month’s macro wrap, we noted early signs that the property sector decline was starting to slow. This trend continued in September, with key metrics showing a more modest decline than in August [Fig 3].

- Real estate investment dropped 9.4% y/y, an improvement from August’s 10.2% fall.

- Home sales by floor space fell 10.6% y/y, compared to a 14.0% drop the previous month.

- Inventory levels grew 20.8% y/y, down from 21.5% growth in August.

In September, new and secondhand home prices fell 6.1% and 9.0% y/y, respectively, with no sign of slowing. Contrary to the negative media headlines, this is actually a positive development, as prices must fall low enough to attract buyers back into the market, which is a prerequisite for the sector’s recovery.

That said, a bottoming out of the real estate sector is many months away, meaning it will continue to drag on growth until early 2025 at the earliest.

All eyes on Beijing

Q3’s economic data paints a mixed picture of China’s economy. A cynic might point to consumption’s record low contribution to GDP growth as evidence that the speed – and quality – of economic expansion has never been weaker. An optimist, meanwhile, could highlight the growth in big-ticket item sales and the steady momentum in industrial activity to argue that economic fundamentals are strong.

In reality, China’s economy is somewhere in between these two viewpoints. Beijing will underscore the reduced role of the property sector, the concurrent rise in high-value manufacturing, and the reduction – albeit slowly – of local government debt risks as evidence that its structural transformation is taking shape. But the missing ingredient is household consumption. Aside from the surge in home appliance sales – likely a short-term boost driven by generous trade-in subsidies – there is very little to cheer about: Income growth has permanently slowed, households’ propensity to consume remains way below pre-pandemic levels, and consumer confidence is near record lows – and still falling.

Investors and businesses are waiting for Beijing to roll out an aggressive fiscal stimulus to boost economic growth and buoy confidence – both preconditions for consumers to ramp up spending. So far, however, the government has relied on a flurry of press conferences and piecemeal policy support, failing to clearly communicate whether there will be such a stimulus, when it will arrive, and how big it will be.

If the government’s support disappoints – as it so often has this year – China’s economy will continue to underperform, and equity markets will quickly drop.

All eyes on Beijing.